Ghost Chapters

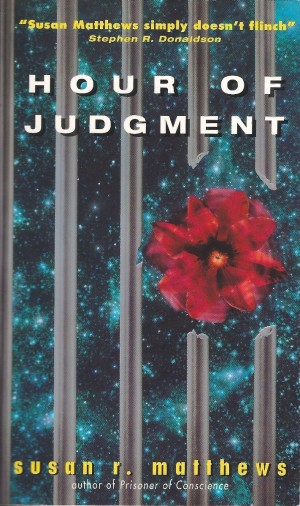

This text is comprised of alternate versions of scenes in =Hour of Judgment= together with a great deal of relationship or character development that was eventually excised for very good reasons (as you will see as you attempt to slog your way through them). Some of the bits of business I quite liked, though.

###

[The novel originally starts out with a heavy whack of relationship & characterization, including this scene of Andrej being all doctor-y, to kind of buffer from the scenes that are coming up of Andrej being anything but.]

###

Eamons sat anxious and still on the levels in her white under-tunic, waiting for the word that would decide her future. The imager that was aimed at her back from close behind her spun its surrogate model within the survey cube on the frame-table, while Andrej squinted cautiously into its depths. Three weeks had passed since Jevan Eamons — a Security troop on the Intelligence Officer’s 3.2 team — had suffered her messy and unfortunate collision with an unsecured crane-lift down in the Ragnarok’s maintenance atmosphere. The damage had been severe but not been hopeless; still, they’d had to wait until the rest of her injuries had been stabilized before the critical reconstruction of the neural networks in her back and neck could be commenced in earnest. Eamons was a young woman, attractive and competent, with a solid career ahead of her; a career that would run into sudden violent shutdown if she were to be unable to go back on Line.

This scan was to tell them which it was to be.

The surrogate stabilized, displaying an enlarged three-dimensional detail of Eamons’ spine at the upper portion of her back. Andrej reached into the survey cube to turn the surrogate in his hands, prying the weightless pseudo-flesh apart carefully. So far, so good; good tendon rebuild, good dense bone recovery. The nerves were what really interested him, of course. That was his part of the job. Smoothing his frown of concentration over into a reassuring face — Eamons was watching him, and he didn’t want to give her the wrong idea — Andrej nodded to the technician to increase the level of detail, so that he could focus on how well the neural network had taken to his surgical intervention.

The surrogate blossomed slowly under his hands, the opaque layers of pseudo-flesh dissolving into a new image on a finer level. Now the image of the primary damage site was as big as the simple spinal cross-section had been before, and Andrej could stroke his fingers down the tertiary romeit process from second to fifth bundle and find it smooth and fat beneath his touch. It had worked, then. The body had forgiven them for the injury. The integrity of the system would recover without recourse to non-organic bridging. Just as well. Andrej didn’t trust cyborg augmentation as far as he could throw it. And he couldn’t throw cyborg augmentation very far. Heavy.

“To me it seems quite promising,” he said to Gille Memakem, who stood beside him studying the recovery-pattern in the survey-cube. Memakem was the most senior physician in the entire Section, and Andrej valued his medical judgment as much as he relied upon Memakem’s administrative skills. It fell to Gille Memakem to keep things well in hand when Andrej himself was away from Section performing what was so euphemistically described as ‘other duties as assigned in support of the Judicial process.’ “Eamons, you must promise me, physical therapy will be very important. But it looks good, what do you think, Gille?”

“He’s happy.” Memakem spoke directly to Eamons, translating for her benefit. It always embarrassed Andrej a little when Gille felt that he had to translate. “He’s got a right to be. But he hates to make any promises, just in case he’s made a mistake for the first time since he’s got here. It looks very solid, Miss Eamons. You’ll be back on Line in no time. Derida, go ahead and escort her to Consult One, I’ll join you there shortly.”

Memakem’s flattery made Andrej even more uncomfortable than his translating, even after all this time. It had been almost four years now since he had been posted to the Jurisdiction Fleet Ship Ragnarok as its Ship’s Surgeon. Almost four years as Memakem’s administrative superior officer, conscious as he was of his relative inexperience. Almost, almost, almost four years. When four years were finally finished he could be gone.

When the last of the eight years that he had sworn to Fleet were finished he would no longer have to serve as Ship’s Inquisitor.

The orderly Derida helped Eamons into her over-blouse, keeping a sharp eye on her range of motion. Wheam — the technician — started shutting down the imager, while Derida escorted Eamons out of the examination area. Putting out his hand to Memakem’s sleeve Andrej drew the man aside, no more comfortable with what he had to say than he had ever been — no matter how many occasions Captain Lowden had provided to him for practice. “There is an assignment for me, Gille. I will not be able to receive the morning reports, you must fill in for me, again.”

Memakem glanced quickly at Andrej’s face and then away toward the wall, keeping his square fleshy face carefully clear of all emotion. “What’s the Level to be this time, your Excellency? Not at the Advanced, I hope.”

Andrej shook his head. “A Sixth Level, bad enough. Conspiracy against the local Judiciary, possibly against Judicial order. But if we’re lucky it won’t go any further than the local charges.”

He was lying when he pretended that he hoped the interrogation would go so far and no further. If he was lucky it would go further, it would go much further, he would have an Eighth Level with which to gratify the obscene lust that had come to define his life. It was polite of Memakem to pretend otherwise, but Memakem knew as well as Andrej did of his shame. The Captain would prefer the Advanced Levels. The Captain always preferred the Advanced Levels, and he owed the Captain for special favors this time — for giving him leave to do his surgery with Eamons, before he went to work. Lowden would have been within his rights to demand Andrej’s immediate attention in Secured Medical. If Lowden had insisted on that, it would have been days and days before Andrej could have faced a surgery; and if they had been forced to delay the neural surgery phase of Eamon’s care by so many as four days past the optimal point the chances of a good success would have been very much diminished. With Eamons’ hopes for her future in Fleet into the bargain.

“Very good, your Excellency.” Memakem gave him the bow in salute, and Andrej returned the courtesy. The surgery was done, Eamons would heal. His prisoner was waiting.

He would call for his Security and begin.

###

Brachi Stildyne had been waiting for the signal for four days past now. He was standing in the exercise area watching one of his teams at drill when the prickling along his shoulders warned him of incoming transmit; then the talk-alert sounded.

“Chief Medical. For Security Chief Stildyne.”

The Security team engaged in combat drill out on the mat floor stopped abruptly in mid-exercise, each of them as tense as a clenched fist. They had all been waiting as well, wondering whose turn it would be this time to accompany his Excellency down to Secured Medical. Wondering when it would begin.

“Security Chief Stildyne, your Excellency.”

“Chief, there is an assignment, I should be started. Who is to meet me?”

Not the team on the floor, no. None of them were bond-involuntaries. Stildyne had his duty team on stand-by, waiting for the time. “Pyotr, your Excellency. Kerenko, Godsalt, Hirsel.” As if Koscuisko didn’t know the assignments as well as he did, by now. “Secured Medical, sir? I’ll dispatch immediately.”

By the time Koscuisko was at the point of getting started he was generally in a hurry to begin. Because he usually managed to put it off until the last possible moment, for one. Because he hated what he did so much, and had to seize what artificial momentum he could create out of an approaching deadline to help impel him forward to his duty. Because once he had surrendered to the inevitability of the requirement he started to get anxious to begin, impatient in anticipation of the pleasures that the torture held for him — profound and intense during the course of the interrogation in direct proportion to how he suffered out of remorse for his cruelty once it was all over.

Stildyne could read that familiar conflict in the little space of measured silence that intervened before Koscuisko spoke again.

“I’ll want the brief from Two, on your way down. Check to see whether she’s got a preference for the recorder.” Less hesitation by the moment, more keen thirst. And yet Koscuisko would not surrender his struggle against himself until he knew that there was no other way. The Intelligence Officer’s brief would specify the crimes of which the prisoner was accused, and of which merely suspected, and provide a lower limit on the required confession to be obtained in language more than clear for a man with Koscuisko’s experience.

To call for the brief so late — so close to starting — meant that Koscuisko was still hoping to maintain his self-control. Pointless, in Stildyne’s view, if commendable. One of the first things that he had learned about his officer was that it was as difficult for Koscuisko himself to stand against his passion as it was for any of his prisoners to resist and to deny him.

“Very good, your Excellency. Stildyne, away.”

Prisoners who succeeded, prisoners who were capable of suffering under Koscuisko’s hand and holding to their truth despite it all were rather rare, and died of the effort — mercifully. As for Koscuisko, Koscuisko still tried to find his way out of his life from time to time. But Koscuisko suffered his passion without the certain knowledge of eventual oblivion that formed a stubborn prisoner’s last defense.

“Carry on, Ivish.” There would be plenty of time later to brood about it, and he nearly always did.

For now he had his orders. Time to move.

###

The place was familiar, after these almost four years — familiar even longer than that, since Scylla had been furnished with a similar standardized facility. Four years on Scylla, although Captain Irshah Parmin had not made much use of his Writ there, apart from lending him out when Fleet politics forced him to accede to Bench requests. Four years on Ragnarok, and Captain Lowden sent him down to Secured Medical with numbing frequency. Andrej knew every corner of the interrogation area by heart, could see each bolted shackle or wall-mount in his sleep; and did, night after night.

It still made him nervous to be here.

Secured Medical was in one of the ship’s stores areas forward, on a storage deck set close beneath the carapace hull of great Ragnarok and well removed from the more well-trafficked corridors in Operations. No one passed by here through the narrow corridors unless they had a specific purpose; it was better that way. A small ready-room separated the theater from the entrance, with an intervening door on interlock with the outer one; so that even if someone did chance to pass — when the door opened, for whatever reason — no one would hear anything of the torture going on, no one would see something they would rather not have thought about. A ready-room, and on the other side of the theater a holding cell for the prisoner. There was a trap in the decking that could be vented directly into ship’s conversion furnaces when mutilated bodies were to be disposed of rather than returned to the civil authority for display. No one ever went into the interrogation theater at all, if they could help it.

And yet for four years Andrej had all but lived here. Exercised himself to torment his Captain’s prisoners for information that meant nothing to him one way or the other. Taken his meals and his lefrols sitting in his chair in the room beyond, considering how next to set his prisoner to suffering. Spent long hours in the night trapped with his own work in his dreams, rehearsing the bloody pattern of his life despite his most desperate efforts to drink himself into so much as a few scant eighths’ worth of sweet oblivion.

Now there was a prisoner waiting for him, and the Protocols to be exercised, and Andrej knew better than anyone that his nervousness was equal parts of reluctance and anticipation. Torture was a horror to contemplate, a horror to face, even if one was to inflict the suffering rather than bear it. Torture was a stain upon his healing, a sin against his own compassionate nature that deprived him of hope and rest alike. But at the same time torture was the single most addictive drug that Andrej Koscuisko had ever been exposed to in all of his medical career, and Captain Lowden’s strict enforcement of the Judicial order provided such a wealth of bright new pain for Andrej’s pleasure that he sometimes thought he had been lost in the black ecstasy of it for his whole life.

Standing at the scroller, Andrej studied the prisoner’s Brief one final time before he went through to his work. A young man of no particular sub-citizenship, a his genotype a mongrel intermix of several lineages of category three hominids. Referred by the Toh Judiciary on Charges of conspiracy to overthrow the Bench — or to assassinate a local Judge, which the Bench tended to treat as an equivalent offense.

Simple enough.

“Very well, gentles, let us be started. Come along, Mr. Pyotr, Mr. Garrity.” He had a thought about how he wanted to begin, already. He only rarely lacked for good ideas, along that line. “Mister Kerenko, is there rhyti? Of course there is. Good man.”

He had his Security here with him, silent and waiting for his word. They were a great comfort to him, his Security were, even though he wanted their actual assistance only rarely for the torture itself. Andrej had never liked involving his Security, not even when Fleet had still posted only bond-involuntary troops — Security slaves — to a Chief Medical Officer’s teams. Things had changed. There were only six bond-involuntary troops assigned to him, now, out of twenty-five in total.

Bond-involuntaries were getting harder to come by every year, but it didn’t matter to Andrej, because he shied away from drawing anyone else into his shame. Partly because of the horror that he had of the idea — people who were required to do anything they were told no matter how abhorrent, or risk the ferocious consequences of a Class Two violation. But mostly out of sheer selfishness, and his desire to have as much of the lovely drug as he could lawfully obtain all for himself.

The inner door that separated the relative safety of the outer room from the uncompromising horror of the inner one slid open beneath his hand.

Andrej stepped through.

“The prisoner, if you please,” he nodded, gesturing to the other door at the far end of the room. It was a bigger room than most of the ship’s work-spaces, if one didn’t count Engineering’s lofty bays or the Security hangars. Bigger than his office, at any rate, bigger than his living quarters, and bare. There was a chair for him on a raised space, padded and comfortable, with his rhyti standing ready for him on the side table. Loosening the first fastening of his duty blouse, Andrej sat down in his chair, to take a glass of rhyti and think about things while Pyotr and Garrity brought his prisoner for him.

Someone else had seen to the preliminary details. The man had already been stripped, and came to him naked and barefoot beneath the token covering of a thin disposable tabard. Security walked him to the middle of the room; Andrej pointed to the place, and Security wrestled the prisoner to his knees, shackling his wrists behind his back before they chained his manacles to the anchor-bolt in the cold unforgiving floor. They were good. Andrej admired their technique. They were efficient. Their task completed, Garrity and Pyotr stepped away from the prisoner to wait for instruction; and Andrej released them with an impatient wave of his hand.

“Yes, thank you, very good. Go away, now. I will call you when I want you.” For his supper, for his rhyti. They were too well trained to show him any reaction, bowing to him politely before they removed themselves; but Andrej knew that they were anxious to be out of there.

It didn’t matter.

The door was closed; he was alone with his prisoner. Alone, and only the Recorder and his rhyti to keep him company. “So.” Eyeing the man over the rim of his upraised rhyti-glass Andrej considered his assignment, distracted by a number of pleasant possibilities. “I am Andrej Koscuisko, and I hold the Writ to which you must answer. Tell to me your name.”

There was no sound in response, although the prisoner seemed to be making an effort. Fear? Or hadn’t he been watered recently? Prisoners were generally kept on meager rations, that was true. Andrej rose to his feet and closed the small distance between his chair and the chained man, offering his tipped glass of rhyti with fastidious care. Yes. Thirsty. He wiped the lip of the glass with his whitesquare and finished it off himself.

“Riveg Ndsi, your Excellency.”

Tentative and fearful, the prisoner found his voice, and Andrej could have smiled at him, fond of him already. No, it would be misinterpreted. “Let us be clear with each other for the Record’s sake. You are on Record. Surely you know better than to answer me like that, when it is the Bench’s Writ that demands your testimony.”

Every decent citizen would know. Such expectations were clearly described and explained in civic briefings at every level, after all. And every citizen less than honest would surely know, too — having had it beaten into them, sooner or later. Generally speaking Andrej had seldom found lack of education to be a problem.

“Yes, your Excellency. Sorry. Ah — the prisoner’s name is Riveg Ndsi, your Excellency — “

So far so good. “Do you know what Charges are Recorded against you, Ndsi? Tell me.”

This prisoner was meek and biddable, as far as that went. Not very far; but Andrej didn’t need much of a start on biddability.

“Ah, there was the Provost Judge. Deserves to die, but — “

An initial intense struggle, an instinct to deny — to assert innocence — in conflict with Andrej’s warning about the Record. Andrej watched with interest as the prisoner called his words back, and started over in a more correct format. “Yes, your Excellency. This prisoner.” It always seemed so difficult for them to use the bluntly impersonal phrasing. So difficult to deny their own individuality with that particular Standard-specific neuter third person, “this prisoner,” instead of “I.” And yet much more would be required of the prisoner before Andrej was done with him, and it would be more difficult, sometimes difficult beyond what Ndsi had probably ever imagined. Andrej had time. He could afford to be indulgent.

“Yes?”

“ — This prisoner is accused of plotting to kill a Judge. Provost Judge. Toh Judiciary.”

Yes, indeed. Andrej set his rhyti glass down and wandered over to the wall behind the chair, almost absentmindedly. He didn’t like opening up his equipment racks until his Security were gone; they had to face enough unpleasantness as it was — most of it from him, or on his behalf. There was no one in the room except for himself and his prisoner, now, and the ever-present Record making its careful tapes of his proceedings. Unlatching one of the racks, Andrej pulled it open and away from the wall, thoughtfully. Drugs, wake-keepers, pain-maintenance. Too early. He left the rack open, though, fully displayed for the prisoner’s benefit as he went for the next one. The prisoner didn’t need to know what the drugs were. Everybody knew about the Controlled List; anybody with any sense would be sensibly terrified to be reminded about the potential horrors that the Controlled List represented.

“What came of these Charges in Preliminary, then? You must have been referred for something.” Other tools, other toys. Firepoints. Three-vices. Eight-straps. Pincers, torcs, clamps. Andrej stroked the shining instruments absentmindedly, his attention divided between his prisoner and his plans for the next few hours.

“Your Excellency. They told — this prisoner — that there was evidence, circumstantial evidence. And an informer. They explained to — this prisoner — that the Bench will not condemn on the basis of what they had, that a confession would be required.”

You’re guilty anyway, so confess. So that we can prove you’re guilty by your own confession. Andrej knew how to interpret Ndsi’s information; the circumstantial evidence was not very strong, and the informer either biased or otherwise unreliable. Yes. “One takes it that you declined to oblige with the confession.”

“I didn’t do anything.” There was genuine pain there, in that spontaneous protest. Andrej was impressed, but otherwise unmoved. For one thing, Ndsi wasn’t Charged with having done anything, only with having plotted — a distinction which frequently escaped the Bench. For another, it really didn’t matter how sincere Ndsi was; there were Charges, and they had to be tested against the Protocols, and that usually resulted in a confession sooner or later. That was the whole idea, after all.

Andrej abandoned a glittering set of three-vices after a final caress and went to yet a third rack, opening it carefully, telling the instruments over in his mind. The handshake. The lictor. The rake, with its multiple tails. The driver, coiled and black and ugly, his close companion from the start of his career in Inquiry. The peony, the ugliest of them all, as thick and smooth of braid as the handshake, almost as long as the driver, heavy as the rake, a whip fit to flay a man alive and kill him in as few as four-and-forty.

“I trust you understand, it is my place to test your claim to its utmost limit. You are referred to me at the Sixth Level, do you know what that means?” Confession had to precede Execution. The peony was for later. For now the prisoner merely bowed his head, stubbornly, and repeated his insistence on his innocence.

“This prisoner is not guilty of any plot. Your Excellency.”

He could start with the handshake, at this level, and move up to the driver, which did require he practice with it constantly or risk going off his form. There would be the truncheon and quite possibly the flensing-knife before he was well finished, perhaps a little of the firepoint. It was the Sixth Level. He could break bone and tear joints, but the firepoint did not truly come into its own until the Seventh, the first of the Execution Levels. The handshake, then, to start.

“Permit me to be the judge of that,” Andrej advised, kindly enough. The handshake, to warm things up. Ndsi’s tabard would tear easily, and presented no real barrier to the lash against bare flesh. One could work more closely, with the handshake, face-to-face with one’s dancing-partner, the better to gauge the progress of the exercise.

“Let us begin at the starting place, then. The Record says you meet with known Free Government sympathizers.” Andrej took the whip up into his hand, raising it to eye-level and saluting its promise with satisfaction. “Be so good as to describe these meetings, to me.”

And wherever they met, whomever they met with, would become by that token equally suspect of Free Government sympathies, but that was nothing to do with Andrej. One had to start somewhere. And the handshake sang like a thrown knife and cut like wire, and his body knew the smell of blood and fear and savored the pain gratefully.

He owed Captain Lowden a favor for permitting him to put this off while he completed his surgical duties.

Andrej Ulexeievitch Koscuisko always repaid his debts in kind, with careful interest.

###

[This was kind of a peculiar scene, came at me from an unexpected angle. At this point I’m unwilling to either confirm or deny its place in the canon. You’ll notice there’s a non-hominid Security troop – I discarded the use of several non-hominid Security troops as distracting from my central focus on the protagonist and his central conflicts.]

###

Godsalt checked the chrono in the door-panel with an absent-minded glance. Shift had changed hours ago, and the officer had been conducting his interrogation for even longer than that. He’d started early on in Second, and it was nearing the end of Third, and that meant fourteen hours at minimum. They would be reaching a crisis point of some sort, Godsalt knew that from experience. Other Inquisitors he had supported broke their Intermediate Level exercises up as much as possible, and only ran at three to four eights at a time. Koscuisko tended to get lost, to forget the hour and run his Inquiries out in one straight bloody line from start to finish. Sometimes Koscuisko didn’t bother to so much as leave Secured Medical for days. It made him all the more efficient, Godsalt supposed.

There were worse ways to spend a duty shift than standing ready with hot rhyti in the antechamber to Secured Medical. VanTalb had a clean uniform folded and set out for Koscuisko when he wanted it; since everything was prepared there was nothing in particular to do. They had to be present. Koscuisko could potentially call for their assistance at any time. Koscuisko very seldom wanted them within, though, so it was almost like an extra rest-shift, really. Almost.

The antechamber was bright and clean, the other members of their team familiar as the situation itself. He was the second senior, Pyotr the senior man; VanTalb of the furry ears and clawed hands was there, and Hirsel at the bottom of the hierarchy, asleep on his feet by the outer door.

Through the open door to the washroom Godsalt could see toweling stashed and ready, a nail-board, a comb, all that a man could want to clean himself. In the beginning — when Koscuisko had first been posted here to Ragnarok, bringing St. Clare with him — he had invariably stopped to wash and change even after the worst of his interrogations, anxious to ensure that his appearance would present no unpleasant hints about where he’d been or what he’d been doing there. Lately it did not seem to matter quite so much. Lately Koscuisko could be in too much of a hurry to get away — to get back to his quarters and seek the numbing distance alcohol provided him — to waste precious time in just washing. It didn’t matter. It was the look on Koscuisko’s face that told the truth of where he had been, and there was no washing that horror out of Koscuisko’s pale eyes, no matter how much time he took to try to set himself to rights before he left.

There was a warning tone at the inner door. Straightening to rest-attention with automatic ease, Godsalt stepped away from the door, alert for the follow-up order. Koscuisko would want his rhyti, or Koscuisko would want other support — a lefrol perhaps, or potentially an extra pair of hands, rare though that was. Or Koscuisko was simply coming out and wanted them to be on guard, so that they would not be unprepared for whatever noise or stench might come from the inner room.

The door parted along its diagonal, sliding open noiselessly. Koscuisko was standing in the doorway, his figure blocking any casual glance into the room beyond. Godsalt kept his gaze fixed respectfully on Koscuisko’s face, making his bow, making his assessment at the same time. There was blood, of course, blood on Koscuisko’s face, blood on his white under-blouse beneath his open duty-tunic, blood on his boots and on his trousers. So much was only to be expected.

Koscuisko was not meeting his eyes, however.

Stepping through the door while it was only half open — Koscuisko could do that, Koscuisko was shorter than the rest of them — Koscuisko struck the door-panel to close it again, turning his back to them, laying his gloved hands on either side of the door and leaning against the wall there with his head down. It was quiet, in the outer room, and Godsalt could hear Koscuisko’s breathing, shaky and gasping, as Koscuisko’s body trembled. He had not finished, then. He had taken as much of a confession as he felt was required; and he had come out now, with his prisoner yet living, holding himself to his own strict standard while he could.

“Duty officer. This is Koscuisko.” The message would go out on a secured line, rather than the standard ship’s dircast. Nothing went out from Secured Medical without careful restriction on its access codes. “Send me a team, to Secured Medical. Support lacerations. Soft tissue damage. Multiple contusions, minor bone damage. A few burn injuries, non-primary in nature. Bleeding, and traumatic shock, and I won’t have Sinspan, do you hear?”

Over the years, Godsalt had learned quite a bit about the Medical staff, being so closely associated with the Chief Medical Officer. Sinspan was not a bad medic; Koscuisko seemed to have a fairly good opinion of her medical skills. But she was dead certain that anyone referred on Charges was getting exactly what they deserved, and not enough of it, which meant that she and her superior officer disagreed on the most basic of levels. Koscuisko didn’t trust her to handle injured prisoners as gently as he liked. Let alone tortured ones.

“Yes, your Excellency. Your team is on its way.”

“Koscuisko away, here.” There was a little catch of hesitation in Koscuisko’s voice as he acknowledged the duty officer’s reply that witnessed to the struggle going on within him. Godsalt had never understood why Koscuisko bothered to school himself against indulgence when seven out of eight times Captain Lowden only sent him back in anyway. Of course it didn’t make any difference whether he understood Koscuisko’s internal struggles or not. Their job was to provide support, not stand in judgment. If Koscuisko wanted to protect the prisoner from the extravagances of his own appetite there were things that they could do, to make it easier —

Pyotr stood to Koscuisko’s left, Godsalt to his right. Meeting Godsalt’s eyes, Pyotr signaled almost imperceptibly. Godsalt matched his movements to Pyotr’s, moving in on Koscuisko where he stood leaning against the wall with his gloved hands leaving bloody smudges against the door-frame. Koscuisko did not protest when they moved him away from the wall, turning him to face into the room away from the theater’s closed door. Meek and unresisting, Koscuisko merely rested himself against them, securely supported by their arms behind his back, weary, exhausted. It was so hard for him to stop once he had got well started. There was all of that energy, all of that passion, checked and thwarted and denied release only because Koscuisko was determined not to indulge his passion — it had to go somewhere.

It was much easier for Koscuisko when they managed to find an outlet for his arousal.

And the clothing would have to come off anyway, with all of that blood. Koscuisko was a fastidious man, under other circumstances. He would not want to be seen in such a filthy uniform.

Godsalt took a handful of Koscuisko’s under-blouse in his free hand, pulling it free from the waistband of Koscuisko’s trousers by the fistful. Pyotr worked the fastenings open down the front of the undergarment, murmuring comfortingly in Koscuisko’s ear, and vanTalb — moving close, in front of them — sniffed at the blood-stains on Koscuisko’s naked chest with interest before setting to work to clean the bare white skin with his raspy feline tongue.

For a long moment it seemed as if it was going to work. Koscuisko submitted himself to their caresses, suffering them to restrain his instinctive gesture of rejection, yielding to the hand that Pyotr put out to turn Koscuisko’s face up for a thirsty kiss whose ferocity expressed — and, if they were lucky, would relieve — the savagery of Koscuisko’s passion, fed and stoked in Inquiry, denied its ultimate expression by Koscuisko’s own misplaced sense of fairness.

And they had made it work, too, from time to time, when Koscuisko was too far gone to want to deny them — but not this time.

Koscuisko turned his head away, his mouth a grim hard self-disgusted grimace. Godsalt could feel the balance of Koscuisko’s weight changing from exhausted and submissive reliance on their arms to hold him up to firm, defiant, self-contained control.

“No. Thank you, gentlemen.”

It wasn’t going to come off, not this time. There was no mistaking that tone of voice, even if it took a second admonition to distract VanTalb from what he was doing. “Be so good as to stand away, I need to wash.”

Godsalt didn’t blame VanTalb; the cat thought with his nose, after all, and body-grooming was offered to seniors by subordinates as a matter of course among VanTalb’s people. Not among Azanry Dolgorukij. Even when Koscuisko was desperate enough to accept offers of comfort under such circumstances he suffered, after the infrequent fact, and accused himself so bitterly of taking indecent liberties with subordinate flesh that the entire incident inevitably took on overtones of rape. It was only the identity of the offending party that varied: Koscuisko accused himself of committing the offense; and Security Chief Stildyne accused Security.

Just as well, perhaps, that Koscuisko had rejected them — there were Chief Stildyne’s feelings to consider, after all. Godsalt knelt to take Koscuisko’s boots, knowing better than to argue. They were lucky that Koscuisko was as tolerant as he was. Others Godsalt had known in Koscuisko’s position had been all too likely to take offense at much lesser liberties than the ones Koscuisko permitted as of no consequence.

In his bare feet now, Koscuisko started for the open washroom door, stumbling a little in his weariness. “Engage the Captain’s scheduler, Pyotr, if you will. I’ll need to make report.” Stripping as he spoke, Koscuisko crushed the discarded clothing across the ready-rail in the washroom piece by piece. “Try for the morning. And send my meal to quarters, I should like to get drunk.”

That went without saying, but Pyotr saluted the washroom door regardless. “Instruction received is instruction implemented, your Excellency.”

Godsalt wondered what Koscuisko’s successor would be like. Captain Lowden had destroyed several Ship’s Inquisitors before Koscuisko had come; which fact was widely held in Security circles to be a significant accomplishment on Lowden’s part, since the Ragnarok had only been on active status for ten years Standard even now.

Was the Captain feeling frustrated, that Koscuisko had lived out his term?

Was that why there had been so many extra exercises, within the past months?

It wasn’t any of his business either way, Godsalt reminded himself. He had the uniform and boots and gloves to turn in for cleaning, and a meal to order up, and he had to be back before Koscuisko was out of the wash-room.

Uniforms and meals were all he was expected to even think about.

###

[A lot of this material was intended to simply demonstrate how far Andrej’s psychological deterioration had gotten since we saw him last at the end of Prisoner of Conscience, where he wasn’t really doing so badly. Didn’t have anything directly to do with the action of the story, but taking it out (because the story didn’t really start until we got to Burkhayden, in a sense) left Andrej’s action for the rest of the novel less well motivated than it might have been, on account of how I didn’t manage to get that psychological frayed edge fully into the remaining text. Live and learn.]

##

Andrej Koscuisko awoke to confusion in the stuffy twilight of a dimly-lit room. Lying on his back, tangled in bedclothes, he stared at the ceiling in dread and dazed wonder for several moments before he realized that he wasn’t alone.

There was someone with him.

There was a monolith filling the doorway between the bedroom and the outer room. A great grotesque statue made up of black horror, and Andrej tried to fathom what it might be, puzzling it out in fits and starts while he struggled with all of the other questions that had to be answered before he could go on.

A monolith, yes. Between two rooms: so there were two rooms there, but that told him nothing. Senior ship’s officers had two rooms to live in. So he was a senior ship’s officer, he knew that, but why should there be a monolith in quarters? What manner of monolith would Engineering tolerate to stand in a doorway between rooms? Wouldn’t it interfere with evacuation, to say nothing of normal traffic patterns?

Oh, this was ridiculous, Andrej told himself, almost too disgusted at his own confusion to be afraid. If the black monolith was friendly he could ask it for breakfast. And if it wasn’t — if the black monolith was Vengeance incarnate, come for him finally after so many years spent wallowing in sin — then there would be no escaping it.

He had to get up.

He tried to move, but he was too thoroughly tangled in bedding to make much headway. The black monolith stirred, finally, and started forward, coalescing from an ambiguous shadow of unknown intent into the familiar and friendly framework that housed the Nurail bond-involuntary Security troop, Robert St. Clare.

“I’ll help you with that, sir. With your permission.”

With the doorway clear there was more light in the room, and Andrej could make more sense of what he saw. The head of the sleep-shelf was in the corner; he could look across the room, to his left, and see the side-table next to the sleep-shelf where he kept his lefrols and liquor, the open doorway into the next room, the half-open doorway into the washroom at the other end. There were the storage closets along the back end of the room where his uniforms were kept, and the icon-table in the far corner.

His uniform was already arrayed in proper order on the valet-stand, waiting for him, but the light from the lamp on the icon-table was dim. It was only enough to point up the sanctimoniously ghastly features of St. Andrej Filial Piety, after whom Andrej had been named. It wasn’t enough to illuminate the ship’s mark on the front right shoulder of the uniform’s over-blouse. No hope for a clue there.

He still didn’t know where he was.

Robert stooped over him, calm and reassuring, working the wadded bedding free from the crevices into which Andrej had compacted it during the course of his uneasy sleep. Robert was safe. He trusted Robert. He could ask.

“Who?”

His voice was a hoarse croak in his own ears. Robert paused in his work of unpacking Andrej from the tangle he’d trapped himself in to take up a flask from the bedside table, holding it carefully for Andrej to drink. It was tepid rhyti, but it was wet. Andrej was grateful.

When the flask was empty he tried again.

“Where are we. What’s going on. What time is it.” Who am I. But he didn’t ask the last one. He already knew some pieces of the answer, and there were good odds he’d have the rest of the information soon enough.

“The officer is Anders, son of Ilex.” Robert’s voice was quiet and soothing, calming without condescending. “Which is to say, sir, his Excellency, Andrej Ulexeievitch Koscuisko. No offense, your Excellency.”

None taken. He and Robert had known each other for too long. Not even the constraint imposed by Robert’s governor could damp the trust and confidence they had in one another: and there was the fact that Robert’s governor had somehow never worked quite right, from the earliest Andrej had known him.

“Out with the rest of it, then, man.” Unlike many of the souls under Jurisdiction, Robert hadn’t learned Standard until quite late in life — his seventeenth year, from what Andrej had gathered. Robert had more of an accent accordingly. It always tickled Andrej’s ear to hear Robert struggle to pronounce his name. “I’m hungry.”

He was fully untangled from his bedclothes, now, and Robert helped Andrej to sit up on the side of the bed, crouching down beside him to steady him where he sat. Robert was much taller than he was. Their faces were still almost on a level. Robert’s face had changed, in the years Andrej had known him; how many years was that?

When he had met Robert, Robert had been short of twenty years Standard, painfully young for the use to which Fleet had condemned him. Robert did not wear a beard even now, since he had no Fleet exception to do so, and Nurail men from Robert’s particular clan-group only grew beards once they were married. There was still no question but that Robert was a grown man, if a young man still. His face had lost weight and gained gravity.

“Oh board of the Jurisdiction Fleet Ship Ragnarok, as the officer please. Fleet Captain Griers Verigson Lowden, commanding.”

Oh, it was bad, then. Captain Lowden. Burying his face in his hands Andrej rubbed at his forehead with his fingertips, trying to massage his brain through his skull. He needed to think.

“And it’s just coming up on first-shift, which means you’re to sit at Mast in three eights. There’s fast-meal. Chief Stildyne will be wanting you for laps.”

Chief Stildyne was always after him for his laps. Andrej wasn’t interested: but he knew that it was one of the things he relied upon to keep him going, to give his life order and meaning in the face of — what?

“And you’re to see Captain after Mast, there’s the Record to be endorsed. Sir.” Robert’s voice was careful and neutral, breaking only momentarily over the word “record” as he helped Andrej to his feet. Yes. That was right. The Record.

It all came back to Andrej, the torture-work that was his life, the soul who lay constrained in agony in Secured Medical even now, the savage greed for pain that their Captain indulged so mercilessly in the name of the Judicial order.

He was Andrej Ulexeievitch Koscuisko, Ship’s Surgeon, Ship’s Inquisitor, on board of Jurisdiction Fleet Ship Ragnarok. He was getting up and getting dressed because he had work to do, and because his fast-meal would get cold.

But there was more.

He had been Ship’s Surgeon for eight years, his term was to expire within two month’s time.

As long as it had been, as horrible as it had been, as many crimes as he had committed in the name of lawful duty, it was over. He was going home.

On his feet, now, Andrej patted Robert’s arm by way of thanks, and staggered off to the washroom under his own power. Free. Two months, and he was going home.

What was to become of Robert and the other bond-involuntary troops once left without protection, exposed to Captain Lowden’s whims by the uncaring indifference of the next Inquisitor assigned?

There was nothing he could do about that.

Andrej switched the wet-shower to its coldest extreme and turned his face up full into its brutal blast to shut the voice of anguished impotence away in his mind. Nothing he could do. He had exhausted all of the options at his disposal, trying. Best not to dwell on it.

He still had two more months to get through somehow before he could go home.

###

[So, you’ll notice that in the previous scene Robert tells us that Andrej’s going to see Captain Lowden after Mast, and here he’s on his way to see the Captain first thing in the morning. Two different drafts. I wrote this thing five, six times, over the course of the years. Continuity has always been a challenge for me.]

###

Morning, and Andrej Koscuisko made his way to his Captain’s office with a short-team escort behind him. He’d had a long night of it, but he’d expected that, so that was just an aggravation — not a problem in and of itself. Captain Lowden was a problem, of course. Captain Lowden was more likely than not to order him back to the torture of Riveg Ndsi, and Andrej had mixed feelings about that. There was that in him which was afraid he would be instructed to return to torture, and hoped that Lowden would not chose to do so, just this once.

And there was that in him which hoped that Captain Lowden would order him back to Secured Medical, and was afraid that he would be denied his treat, this time.

Command Administrative was a quieter area than most, fewer people, wider corridors — room enough for four people to walk abreast, perhaps — and deep within the shielded core of one the Ragnarok’s operations areas. Andrej stopped in front of the Captain’s office door, waiting while his man Garrity announced him.

“Chief Medical Officer reports to Captain Lowden. As scheduled, review of interrogation exercise.”

Two Security flanked the doorway on standard post, and one of them Andrej knew — Janisib, tall and brown and formidable. She had been on one of his teams when he’d got here, and she’d done him good duty for a year or more; but the work had gotten to be too much for her. Since she wasn’t bond involuntary she’d been allowed to transfer, and Andrej hadn’t blamed her. Her decision had come shortly after she’d been posted with him on a set of field exercises. Those could be among the most difficult for Security because they had to be improvised.

The work was too much for him, at least in a sense, but he was not permitted to transfer out — not until his term was up. Only a matter of weeks, now, and his father had not forbidden him to leave, had not required that he extend his sworn commitment. It didn’t matter to Andrej any more if his father thought he was a coward. All he wanted to do was get away. Janisib had gotten away; and if there was anything she was it wasn’t any kind of a coward.

The doors slid open, and he winked up at her broad silent face and went through.

Lowden was finishing some document or other with his back turned to the room, studying the reader. There was fast-meal set out on the broad-board against the wall, Andrej was glad to note. He’d had breakfast, yes, but he was still hungry — or perhaps he’d not quite had breakfast, perhaps he hadn’t managed to keep anything down for the past few hours. That would explain being hungry, for a fact. There were plenty of his favorites here, fatmeat, brodtoast, rhyti, fruit, sweetspread. Captain Lowden was a thoroughly contemptible man, and he had done his best to make Andrej’s life a ceaseless torment for the past four years, and he had done a very good job of it, too. On the other hand he did take good care of his Chief Medical Officer — in his own perverted fashion.

Andrej piled a palm-sized plate full of little snacks, all of them less than healthy for a man, and took a seat at the conference-rail, licking sugar-frosting off of the fingers of one hand absentmindedly. Rhyti was a wonderful thing. One felt a new man.

Lowden turned in his chair, as if he’d only just now realized that he was no longer alone. “Good greeting to you, Andrej, have you slept well?”

As if Lowden didn’t know. Andrej waved a bit of pastry at the Captain in response, swallowing a mouthful of hot sweet rhyti before he answered. “As any sinner. You’ve had a look at the cube, I imagine.”

Now Lowden dropped his gaze, turning his head down to look at his desk. The lights picked up the red in Lowden’s brown hair; he was getting old, Andrej noted uncharitably. He’d be completely red-haired in no time. “Well, now, Andrej, I need to speak to you, about that.”

Of course he did. Captain Lowden was as obvious as he was tall; and he was very tall. Not as tall as Wheatfields, no, of course not — Lowden could stand up straight even in quarters without knocking his head against the light-fixtures. The fact remained; Andrej could see right through him. He took a few bites of fatmeat, waiting.

“There’s a little confusion here, Andrej, don’t you think? I mean, this man, he was referred on conspiracy. I know that starts at the Sixth Level, Andrej, but it looks as if you left it there. Am I missing something?”

Yes, naturally he was missing something. He was missing the torture that he so enjoyed, the blood and the screaming. But Andrej could not honestly contemn him for that — not when they had so much in common. “The confession should have been appended, Captain, is your copy of the Record not complete?”

He was being provoking, and he knew it. But he was drunk, and tired, and Lowden would do whatever Lowden had decided to do no matter what Andrej had said to him about it. There were only a few more months, only a matter of weeks . . .

Now Lowden let himself show irritation. “There’s a confession, all right, Andrej. But I wouldn’t have expected you to turn in such an incomplete piece of work. I’m sorry to have to say this. I understand how hard it must be for you to keep your mind on your duty when you’re so close to being relieved of your assigned tasks. I’m still forced to describe the conduct of this interrogation as unprofessional.”

As if Andrej cared. As if Lowden were an authority figure, a parental figure, to whose disapproval Andrej would be vulnerable. Lowden was an authority figure of a sort, to be sure. But Andrej despised him too much to be moved by his transparent attempts at psychological manipulation.

“Is it indeed so, Captain Lowden? And here I had thought, there are the Charges, here is the confession as Charged, we are finished.”

The Captain pushed himself away from the desk, going over to the fast-meal service for a glass of annerbe-solution. Andrej rather wished Lowden hadn’t chosen annerbe; the milky fluid invariably ended up in Lowden’s pathetic excuse for a mustache, emphasizing the sparseness of the growth and Lowden’s casual disdain for good grooming at one and the same time. If a man was going to drink annerbe-solution the least a man could do was remember the use and function of a napkin. On the other hand it was hardly Andrej’s place to say as much, even as close — as intimate — as he and his great good friend and guide had been, these four years past.

“And that’s good enough for most people, Andrej, that’s true.” Sitting down across from Andrej, now, Lowden leaned forward, confidentially. “But you’re better than that, and we both know it. I can’t pretend that what’s acceptable from anyone else is anything like up to your standard.”

The admonitory tone was really wonderful. Believable. One of Lowden’s very best tricks. And it did make Andrej feel regretful, right enough — not the tone of voice, so much, not the words, but the fact that the closer Captain Lowden was to him the more difficult it was for Andrej to ignore how much he hated Lowden for what he had put Andrej to. For himself, but also for all of the prisoners Lowden had dug up for him, demanding proofs of guilt, degrees of Execution, the constant exercise of the Protocols in all their horror. It was difficult to enjoy his fast-meal treats with Lowden so close to him.

“Now, I want you to just go back and finish the job up right, Andrej. I know you can be a professional about this if you just put your mind to it.”

There it was, and it turned the delicious oily savor of the fatmeat into a leaden ball of acid in Andrej’s belly. “What for? There isn’t anything else there. Captain.”

“How can you say that? Even I know better than that, Andrej — ”

And Lowden did “know better,” right enough. Lowden had studied the Protocols, knew them as well as Andrej himself did. Because Lowden enjoyed them. Because Lowden liked to watch. “There’s an entire section of implied collaterals when there’s been a confession of local plotting, Andrej. And you didn’t even ask him about his family, his friends, anything else. Nothing. You’re losing it.”

He hadn’t asked, no. At the end of a properly executed Sixth Level the answer to any question would be an affirmative one, because the pain was so bad that the fear of more pain removed any realization of endangering others from all but the very most stubborn of minds. Or from Nurail. Andrej remembered in the Domitt prison, while he’d been with Scylla — one of his prisoners, somebody’s father, with a potentially politically dangerous son at large. The bargain they had made. His pledge not to ask, if the man could only manage to keep fair silence long enough. Until whomever’s father had no longer been capable of speech coherent enough to condemn anyone; and then Andrej had asked, and sent the man to his death with his family still unidentified and unlocated. At fearful cost to himself, but the Nurail had done it . . .

“I didn’t ask for implied collaterals because I don’t think there are any. It’s a clear confession. Implied collaterals are only required at the next Level, Captain. Which you know, of course.”

And they both knew what Lowden’s response would be. And they both knew that Andrej had no legal recourse but to obey.

“You’re not looking hard enough, you’re going soft, but you’re still on active status, Andrej. Command elevation. Take it to the Seventh Level, and give me those names.”

He couldn’t swear to certainty that there were not names to get, no, he could be mistaken about that. There could be information, hidden there. It was just possible that there were Free Government plots to be exposed. Andrej didn’t think so. The only real issue was Captain Lowden’s private greed, and the implication — and subsequent torture, murder — of possibly innocent people. If Lowden demanded names Andrej would get names, they both knew that. Andrej could get anything he wanted from Ndsi, at this point. It wasn’t what he wanted that was at issue; and Lowden knew exactly how to bring Andrej around, Andrej had to grant him that, ungrudgingly.

“Yes, but which do you want more? The names? Or the Seventh Level?”

Ndsi was a pawn, now, nothing more. The poor victim of Captain Lowden’s lust, and Andrej’s lust as well. Lowden clearly meant for him to die, one way or the other. If Lowden mandated implied collaterals Andrej would have to implement, and there would be more victims. But Lowden could usually be persuaded to let Andrej whore for him, instead, and if it meant Hell for Ndsi at least it did not mean as much for every unfortunate whose name a tortured man could bring to mind and put on Record in a mindless and insane attempt to please his torturer and make it stop.

“Andrej, you shouldn’t even joke like that. You know better.” Lowden didn’t bother to hide his self-satisfied smile, rising to his feet, towering over Andrej where he sat to give one of his shoulders an indulgent shake. “We never take such a drastic step without a clear Judicial mandate, never. Think of what it means to your prisoner, after all. But — under the circumstances — ”

Yes, of course. Under the circumstances.

“ — if you haven’t gotten anywhere with implied collaterals by the middle of the Eighth, Andrej, I’m afraid we’ll have to admit defeat. We simply can’t justify going any further than that without results.”

The Eighth Level, the middle of the Advanced. Andrej drained his flask of rhyti and set it down on a side-table, with his half-emptied plate. The Eighth Level . . . but at least they were half-way there, already. And there would not be any more names, not from this interrogation. Andrej was willing to accept an Eighth Level, unfair as it was to Ndsi. He had no other option but to terminate prematurely, under cover of an accident. The first time he’d tried that way out with Captain Lowden had been the last. Captain Lowden had seen to it that every single one of Andrej’s bond-involuntary Security was put on Report and threatened with Charges, and Andrej had realized even so long ago that the Captain was more than a match for him.

“How much of an Eighth Level does the Captain consider appropriate, prior to termination?”

He didn’t like thinking about what it had cost him to keep them from the whip. He certainly could not afford to give Lowden cause to threaten his Security again, since he would not be here much longer to plead for an Exception.

“Well, now, that’s not an easy question, is it?” Lowden would know exactly what was going on in Andrej’s mind. They understood each other far too well — to Andrej’s shame. “It’s a pretty solid Sixth. I’d say — take a couple of hours at the Eighth Level, then terminate. Let’s make it four eights at the Eighth Level, you can manage that, Andrej, can’t you?”

Of course he could. And part of him would even enjoy it. “I’d like to check into Section for an hour or so before I continue. With the Captain’s permission.” He didn’t have any impudence left in him, not any more. It wasn’t as though it was a game between he and Captain Lowden. Or even though it was a game it was other people who would suffer as a result of Lowden’s frustrated displeasure, and that took all of the sport out of the contest.

“Don’t wait too long, Andrej. I’ll want a complete Record from you by Second next, day after tomorrow. That’ll be all.”

Back at his desk, now, Lowden turned his attention to something on his screen, and Andrej bowed to Lowden’s oblivious back and left the room. What did it matter, if Lowden should dismiss him like a servant? He was a servant, a lackey, an errand-boy. A whore. Captain Lowden’s whore. And because Captain Lowden cherished tapes of inhuman torture, he had just agreed to brutalize a man who had already confessed, merely to try to keep yet more names off Record. If he could keep anyone’s name off Record, at all. If the Bench hadn’t already taken everyone who might know anything about Ndsi’s supposed plots in hand, and to the torture . . .

Jan was trying to catch his eye, but he had no humor now to wink at her.

An hour in Section, to update Memakem.

And then he would go back to Secured Medical, and it would start all over again. Two days, and four hours to be at the Eighth Level. Time stopped for the tormented, and there were no hours for people in such pain that centuries could pass between the drawing of one breath and the next, the outraged spirit reluctant to keep breathing. Four hours was as good as four weeks, four months, four years. Two days was an eternity.

Only a few more weeks, and he could go home, and be done with such horrors for the rest of his life.

A few more weeks.

He had to survive for just a few more weeks.

###

[It’s an interesting dynamic between Andrej and Lowden, because there’s an extent to which Lowden really does take very good care of Andrej Koscuisko. In a sick and twisted sense. I’m not saying he didn’t deserve to die, mind you.]

###

Ralph Mendez presided over Ship’s Disciplinary Hearing once a week, whether he needed to or not. As the senior Security officer on board it fell to him to review the periodic roster of offenses reported, violations committed, adjustments required in the day-to-day workings of a ship of war; and the Ragnarok — was not one. No, the Ragnarok was an experimental ship still in the final stages of proving out its still-controversial black-hull technology and a sixteen atop thirty-two lesser innovations: but there was discipline to be maintained all the same. Ship’s First Officer, Ralph Manil Mendez, son and grandson of men so named, to sit in judgment. Ship’s Inquisitor, Andrej Koscuisko, to weigh the penalty, because the only Bench officer on board was the Chief Medical Officer, and Koscuisko would be tasked with the administration of any corporal punishment deemed appropriate. Or its delegation; but Koscuisko was selfish about the beatings, and held them all for himself. Four years ago Mendez had supposed that was because Koscuisko had a particular taste for the work. Koscuisko claimed that as his excuse still.

Mendez no longer quite believed him.

Six-and-sixty at Koscuisko’s hand was brutal, was ferocious punishment, but it was survivable — Mendez had seen that. Six-and-sixty from anybody else was a death sentence. Koscuisko knew what he was doing with a whip.

That was why the Bench had first mandated the restriction and ruled that only medical officers were to execute the Protocols.

Ship’s First, the Chief Medical Officer, and usually some representative from Command Branch sat at Ship’s Disciplinary Hearing to round out the panel. Today it was the senior of two third lieutenants on board, Jennet ap Rhiannon, crèche-bred, newly assigned, and a little impatient. Koscuisko wasn’t quite arrived, not yet.

“We have — how many cases this morning, First Officer?” ap Rhiannon asked carefully, reaching across the table for the rack of cubes. “Five?”

Crèche-bred Command Branch. A tricky piece of business, the third lieutenant, short, stocky, dark hair, full oval face, blue eyes. More or less. No nonsense about her, but she was polite; she hadn’t asked him why Koscuisko was late, not in so many words. So far.

Koscuisko was just now coming through the far doors into the senior mess room that served for this and other administrative functions between the four meals that the ship served daily. It was early on in Koscuisko’s most recent interrogation, Mendez noted; Koscuisko still seemed fairly fresh and rested. Clean linen was a universal restorative, and Koscuisko’s people took good care of him — as Koscuisko of them.

“My excuses, First Officer, I mean to say apologies. I have overslept. It is not Robert’s fault, he tried to wake me, and I believe I have locked him into the wardrobe. Good-greeting, Lieutenant, ap Rhiannon I think?”

ap Rhiannon was on her feet, politely standing to attention for the entry of a superior officer. Koscuisko nodded to her, climbing the low steps that separated the back end of the mess area on its raised platform from the more general area where the senior warrants and junior officers took their meals. Yes, brisk and genial, and unless a man knew to look he could easily miss the fathomless pit of desperation behind Koscuisko’s pale eyes entirely.

“I hate it when that happens,” Mendez replied, to make conversation. “Hope you remembered to let him out, Andrej, he’ll get a crick in his neck. Well.”

Koscuisko took his seat to Mendez’ left, on the middle of the board. ap Rhiannon waited till Koscuisko had settled himself to sit down. Mendez caught ap Rhiannon’s gaze lingering on Koscuisko’s face as she sat, and suppressed a grin of recognition. Yes, Koscuisko let his hair go out of Standard tolerance from time to time. No, it wasn’t up to any Command Branch officer on board except for Captain Lowden himself to say anything to Koscuisko about it.

“I saw Wheatfields in the corridor, First Officer, perhaps if we started in Engineering and got it out of the way?” Koscuisko suggested.

Naturally Koscuisko wanted Wheatfields well clear of the area before he left the room. In the four years that Koscuisko had served on board of Ragnarok he had gradually developed a relationship of grudging mutual respect with the moody Chigan whose partner had been murdered by one of Koscuisko’s fellows so many years ago. Wheatfields still had a tendency to knock Koscuisko into the nearest wall from time to time for no particular reason. It was nothing personal.

Mendez nodded at the lieutenant. She called out to the sergeant at arms, her voice clear and neutral — chilling, almost, in its professionalism.

“His Excellency, Serge of Wheatfields, Ship’s Engineer. Willful disregard for standard repair procedures on status checks resulting in avoidable physical damage to the fabric of this ship.”

Ship’s Engineer had to duck his over-tall Chigan head to step into the room. The accused came behind his senior officer under Security escort; a junior maintenance tech, pale but defiant. Mendez had the scenario at once. Wheatfields was past his patience, and wanted to make the point with the technician; who — to judge by his previous history at Mast — had an attention deficit disorder of some sort.

“Technician second class Hixson. State your name, your identification, and the nature of the issue on which you have been called to answer.”

Koscuisko’s turn. Chief Medical knew the formal legal language cold, and could probably recite it in his sleep. It should have given Hixson pause to realize that he was faced with the man who held the Writ to Inquire on Ragnarok. Unfortunately Hixson did not seem to be impressed.

“Yes, your Excellency. Sallie Hixson, as previously identified. Gross structural components forward, carapace hull, third-shift. Sir.” Hixson sounded bored: careful enough to express all due respect, but beneath it all — as he finished his recitation — Hixson clearly was not convinced that what he’d done was all that important to the safety of the ship.

“Towards the end of duty shift two days ago this troop failed to complete items sixteen through twenty on pre-seal survey and failed to so note on documentation, falsely attesting to completion of task. Bulkhead subsequently failed under random test, resulting in physical damage to fabric of ship. Sir.”

Mendez could empathize, to a certain extent. If Hixson had never served under fire he had no personal experience of catastrophic hull failure during a firefight. Unfortunately there was no margin under Fleet protocols for learning the serious nature of a hull failure on the job: a person was expected to take it as a given.

“Third offense,” Wheatfields reminded them, just in case they hadn’t noticed from the record. “You’ll remember the conversation we had last time, Hixson?”

It was for Koscuisko to carry the inquiry forward, but Koscuisko prudently kept shut. This had more to do with Engineering anyway.

“Yes, your Excellency.” Hixson had begun to sweat a little. “But, ah, under the circumstances, sir. No harm done, after all, no need for extreme sanctions.”

“I decide whether or not harm was done, Technician.” Mendez was impressed. Wheatfields was angry. “We were lucky. You could have gotten someone killed.” Wheatfields had been standing behind Hixson and his escort, while Hixson made his statement. Now Wheatfields closed the distance between the accused and the Bar. “You and I have had this conversation before and I’m tired of hearing excuses. We agreed on assessment of penalty last time, Hixson.”

Mendez checked his ticket, casually. Yes. They had. Wheatfields had waived his right to demand blood. Hixson had promised it wouldn’t happen again.

“Yes, sir. We did, sir. Guilty as charged, sir.”

Not as if that would make a difference if Wheatfields had decided to give up on Hixson. Ship’s Engineer was within his rights to summarily dismiss Hixson from duty in section on board of Ragnarok, forever. That would mean reassignment for Hixson, under less than auspicious circumstances. And Hixson had just about exhausted his issued ration of second chances before he’d even got to the Ragnarok.

Wheatfields turned around, away from Hixson, nose-to-nose with Koscuisko where he sat, leaning over the table from the other side. Koscuisko did a good job of not looking startled. “What’s my range, Chief Medical?”

Technically speaking — once again — that was up to the Bench officer to decide. Koscuisko just frowned a little, thinking. “Couldn’t really see one-and-ten at this point, Serge. You’re going to have to start at two-and-twenty. It’ll take up to eight-and-eighty, depending on how dangerous the failure might hypothetically have been. But that’s pushing it.”

Koscuisko spoke quietly, but it was a small room. Still Hixson had been warned: and if Hixson couldn’t quite believe that he could be put to death for faking a check-off list on an inspection chit he was a least beginning to think a little harder about why inspection chits were important.

“I want four-and-forty from the son of a bitch,” Wheatfields said firmly. “It’s going to take four shifts to get structural integrity restored along that piece of wall. But I want him back on duty before we make Burkhayden, too.”

“You’ll have to make do with three-and-thirty, then.” Koscuisko’s voice was regretful, but firm — as if he wasn’t simply stating what Wheatfields had been after all along. “Three-and-thirty, and I can see return to duty in five days. Deal?”

Three-and-thirty was enough to get anyone’s attention, whether or not the Bench standard saw it the same way. Mendez cleared his throat. This was his Mast, after all, when it came down to it.

“All right. Hixson, your senior officer has asked for three-and-thirty in consideration of the failure in duty you have acknowledged. Chief Medical states five days are to be provided for recovery.” If Hixson had been bond-involuntary, now, rather than a free man, Lowden would cut that recovery time in half as a matter of course. “What’s your call?”

“Sir. Chief Engineer is within his rights, sir, we had agreed. Just and judicious that it should be so, First Officer, three-and-thirty prudent and proper as penalty. Sir.”

Maybe it would work.

Hixson wasn’t stupid. He could interpret negotiation as well as anyone. Wheatfields wanted to salvage him for the Ragnarok. But Wheatfields was tired of making excuses for him.

“Let the Record show, then. Thank you, gentles, return Hixson to duty-ward pending execution of penalty assessed. Good-greeting, Serge.”

One down.

Four to go.

“Next.”

All fairly innocuous, especially after the first. Brawling in common-room over an opprobrious name which might or might not have been spoken aloud. Extra duty to be performed to balance out having evaded an assigned duty shift without taking adequate care to ensure that arrangements for coverage were honored.

Sloppy cleaning in the recyclers in mess leading to the loss of a day’s run on one of the ration lines, no great loss as far as Mendez was concerned but rules were rules. Extra maintenance for three weeks to be performed by one of Two’s people, caught napping on duty station after celebrating too hard over a co-worker’s promotion.

This was the daily stuff of discipline and punishment on a ship of war, and if it hadn’t been for the relatively unusual occurrence of Wheatfields’ invocation of corporal punishment Mendez could have slept through it himself and not felt any harm done.

“That’s it for today, then?” Koscuisko asked, gathering a set of disposition tickets into his left hand as he rose. “I’ll take these to Captain, First Officer, I’m on the agenda anyway. Lieutenant.”

ap Rhiannon stood in turn a little abruptly, as though surprised at Koscuisko’s relative informality. She was new. And crèche-bred stood on their dignity far more frequently than even other Command Branch officers. Mendez was perfectly comfortable with letting Koscuisko take the report forward: he and Captain Lowden had years of negotiation between them, now, they had it down to a fine art.

“Captain will go with three-and-thirty, do you think? Andrej?”

Captain Lowden was a relatively strict disciplinarian: prior to Koscuisko’s arrival had been a ferociously strict, by-the-book assessor of the maximum available penalty for a given offense. That was part of the negotiations between Koscuisko and the Captain that had nothing to do with any softening on Lowden’s part and everything to do with the alternative entertainment Koscuisko could offer down in Secured Medical to while away the long hours of Lowden’s usually uneventful days.

Mendez knew it went on.

He just didn’t want to know anything more about it, since there wasn’t anything he could do.

“Good odds, First Officer, depending. I think it’ll be all right. Good-greeting, I’m late.”

The door at the far end of the room closed behind Koscuisko’s back.

Jennet ap Rhiannon sat back down.

Mendez waited, curious as to what she would say.

“There’s a prisoner in Secured Medical, First Officer.” Interesting choice. No question about why it was Ship’s First who asked Chief Medical about what decision the Captain would make on a disciplinary issue, rather than the other way around. “This is the first time I’ve been assigned to a rated warship. I’d like to have a look at what goes on, as long as there’s an Inquiry in process.”

She’d already been to Secured Medical to have a look, in fact — Mendez had Stildyne’s morning report. But Secured Medical was just that: secured. Nobody went into Secured Medical without prior and explicit authorization from Chief Medical.

To her credit she hadn’t tried to bully her way past the bond-involuntary Security on watch over the prisoner.

“Surely they covered it in orientation, Lieutenant.” That didn’t mean he had to make things easy for her. It was bad enough that the Captain treated Koscuisko’s Judicial function as recreation. There was no reason to tolerate any similar tendency in junior officers. “What’s to see?”

The lieutenant frowned. “True, First Officer. But I’ve been active now for four, five years. And if I’m to be responsible, one day, I’d like to know what I’m to be responsible for.”

All right, maybe it wasn’t prurient interest, maybe it was a misplaced sense of responsibility. “Best bet is to let Stildyne know, he can pass the word on to his officer. I’ll tell Chief, Lieutenant. Is that all?”

Koscuisko’s Chief of Security could find the best time to put her request before Koscuisko. Koscuisko listened to Stildyne. Koscuisko didn’t listen to lieutenants, Command Branch or no. Koscuisko hardly listened to him, Ralph Mendez, and he was senior; it wasn’t insubordination, though, not really. Captain Lowden simply kept Koscuisko strung out too taut to operate on anything more than a very basic level.

“Thank you, your Excellency.”

If Koscuisko got Lowden to accept so mild a punishment as three-and-thirty for Wheatfields’ technician it would be because Lowden expected to split the difference with the prisoner in Secured Medical —

None of his business.

And nothing he could do about it either way.

Ralph Mendez put the familiar resentment away and left the room to return to his office and prepare for staff in two eights.

###

[The foregoing scene just disappeared from the final text, though – again – I thought it was interesting from a Day in the Life sort of point of view. The following scene is in the final text, but from Lowden’s point of view, and I like Ralph’s point of view, and appreciate my chances to use it.]

###

Command Branch and Ship’s Primes, Jurisdiction Fleet Ship Ragnarok. Captain Griers Verigson Lowden, commanding. Ship’s Executive Ralph Manil Mendez, Third, bored halfway to sundown, and disgusted with the lot of them.

Not their fault, of course, Mendez reminded himself, cocking an eye down the staff table at his fellows. Not Wheatfields’ fault, the Engineer kept to his own corridors and minded his own business. Not the Intelligence Officer’s fault, either. Two was actually more of a help to him than anyone else here, even if she did look like an oversized vulpine with the great leathery wings of a night-glider. As near as Mendez had ever been able to figure out Two had no hidden agendas, no disguised motives; and that made her unique, on board this ship.

Two caught his eye and clashed the sharp white teeth in her delicate black muzzle in his direction, cheerfully. Mendez was not about to let himself be cajoled out of his mood, however. For one, Memakem was sitting in for Koscuisko again, and everyone knew what that meant. For another Lowden was late, as always, and as obvious as the unsubtle reminder of rank had always been it frequently still managed to aggravate Mendez. He had work to do, and more than he should have, in his estimation. The political games that Command Branch seemed to relish with such enjoyment were all so much dried-up day-old dung to Ralph Mendez.

The door to the officer’s mess room opened, and Mendez glanced up across the room to confirm identity before he bothered to stand up. He didn’t need Ship’s Third Lieutenant to remind him. Of course ap Rhiannon was required to call the command anyway.

“Stand to attention for the Captain, Lowden, commanding.”

She got the job of calling it because she was the junior Command Branch officer here, but if Brem and Wyrlann — Ship’s Second and First Lieutenants, respectively — expected her junior status to keep her in her subordinate place they had another think coming. Brem and Wyrlann were technically senior, true. But ap Rhiannon was crèche-bred, and crèche-bred Command Branch were sewer sharks in Fleet braid. Acid ambition and the cold certainty of absolute authority were fed into them almost from their birth. Captain Lowden didn’t pay her any mind, but Lowden probably was safe even from crèche-bred Command Branch, with his connections. It was the other officers without powerful friends whose interests were at risk.

“Good greeting, good greeting. Be seated.” Lowden was never in a hurry to step up to the table, to give the at-ease. Ralph Mendez was too old to care one way or the other, and their guests were Bench Intelligence, too professional to show a hint of any sort of feeling whatever. He wondered what Two knew about them.

Taking his time, again, Lowden poured himself a dish of vellme before he proceeded. “Well, we’ve got a pretty full list, here, today. And I don’t want to keep any of you, I know you’re all busy.” Which was, of course, why he was late. Because they were busy. Because he could make them wait. Getting irritated about it only played to Lowden’s rules. “Let’s have report, shall we? Ralph?”

That’s First Officer to you, son, Mendez thought. You useless excuse for a Ship’s Captain. “Nothing to report, your Excellency. Maintenance on schedule, readiness status at Line standard.” It wasn’t really fair of him to feel that way about Captain Lowden, though, not really. He wasn’t an ineffective Captain. He just wasn’t one that Mendez could have any respect for, and that was for purely personal reasons, not any professional failing on Lowden’s part. “No major infractions during the last period. Inventory down five in Engineering, three in Intelligence, eight in Security, five in Medical.”

“Eight in Security?” Yes, he’d expected a question from Lowden on that one. “I thought we were only expecting seven replacements.”

“There’s a Fleet requisition out for Chief Stildyne, your Excellency. New from day before yesterday. He’s offered an Executive slot on the Edeslock Line, JFS Sceppan.”

And Lowden thought it was funny. Too bad. But Lowden just couldn’t seem to let Koscuisko be, whether Koscuisko was there or not. “Oh, our good Chief Medical isn’t going to like that, is he? I mean what with their close personal relationship, and all. Has Andrej been notified? No, that’s right. He’s — busy.”